The PSA courtroom over a ten-year period: Following the guidelines is essential

By Prof. Chris Bangma (Rotterdam, NL) and Dr. Lionne Venderbos (Rotterdam, NL)

Prof. Chris Bangma co-chairs the Nightmare session on early detection of prostate cancer, the first Plenary session of EAU21 Virtual. This session will be broadcast live from our studio on Friday 9 July from 10:30 – 12:00 hours. By way of introduction, Prof. Bangma wrote this article in collaboration with his colleague Dr. Lionne Venderbos.

The awareness of PSA has resulted in an increasing number of men requesting a PSA test. Public news sources mention the good results of prostate cancer treatments, while health authorities are stressing the importance of early diagnosis and prevention of diseases. Therefore, general physicians (GPs) and urologists deal with men wanting to know their PSA on a daily basis. Not always are those requests regarded as appropriate or relevant.

Sometimes the decision is straightforward, for instance in case of the 80-year-old cardiac cripple who wants to prevent prostate cancer. There is no way screening is going to alter the life expectancy of the aged, asymptomatic person with a high comorbidity. As various health authorities doubt the benefit of population-based screening (for example the United States Preventive Services Task Force and the Dutch Health Advisory Board in the Netherlands), it is complex for GPs to advise their asymptomatic patients on their requests to screen at an early age. This sometimes results in a decision not to measure PSA, followed by later regrets of the patient in case prostate cancer is diagnosed at a non-curable-disease stage. Legal claims hide around the corner, and a protracted stressful period lies ahead of the patient and his physician.

PSA court cases in the Netherlands

As the frequency of prostate cancer and early detection in our practices is high and the public discussion about the value of PSA is intense, we retrospectively regarded the court cases related to PSA in The Netherlands over the last decade. Population-based screening and the active offering of individual PSA-based screening for prostate cancer are legally forbidden in the Netherlands (in order to protect its population against overzealous medical practice). It is however permitted to screen when a person is requesting this himself and is well-informed about the pros and cons of screening. PSA testing is also reimbursed. In the Netherlands, prostate cancer is annually diagnosed in 12.000 men over a total population of 17 million (of which 8.6 million are men and ±3.5 million in the age range of 45-80 years) [1]. PSA-based testing is likely to take place in around 50.000 men annually. Given this background, there is a need to carefully follow the official professional guidelines related to the use of PSA. However, such rules may also provide fertile ground for legal complaints and judgements in court.

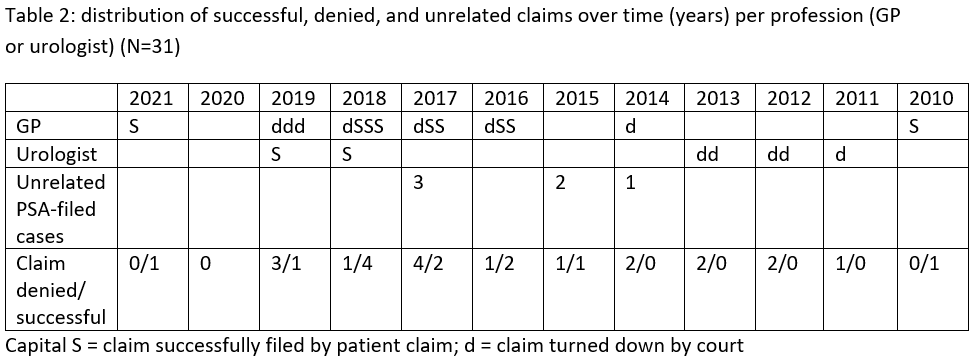

All court cases in the Netherlands are public and digitally accessible via www.tuchtrecht.nl. During the period 2010-2019, 31 cases were published related to PSA management. We analysed all cases and tried to answer the following questions:

- What was the distribution amongst health professionals?

- What was the incidence over time?

- Which basic legal principles did determine the outcome of the cases?

- Which professional guidelines were used for the legal judgments?

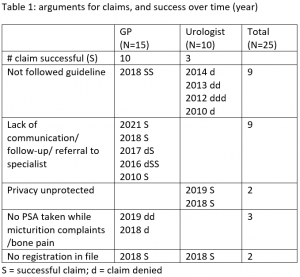

We classified and summarised the cases (incidentally with up to 9 separate claims) in the table below and illustrated our findings with three cases for educational purposes.

The results of a conviction varied between an official warning and a criminal punishment (which only happened in 1 case). Most convictions were published in the Dutch State Journal and offered for publication to the Dutch Journal of Medical Legislation.

Three cases for educational purposes

- Case 22. Claimer reproaches the GP for not having referred him to a urologist 5 years previously with complaints of recurrent haemospermia. He was diagnosed recently by a second GP with prostate cancer staged T3. Also, the initial GP failed to discuss his strategy of conservative management with the patient and also failed to register this in the patient file. Court decision: the lack of referral is regarded as limited carefulness, however not culpable. Missing a diagnosis is not illegal. But the lack of discussion and registration in the patient file is culpable. The court assigns the claim and gives an official warning that will be published.

- Case 17. Claimer of 73 years old reproaches the GP for not having performed a PSA measurement despite his micturition complaints. He has recently been diagnosed with metastatic PCa. Court decision: the GP has acted according to the guidelines on benign prostatic hyperplasia. The claimer had not made any earlier requests to screen on PCa. The claim is rejected.

- Case 3. Claimer reproaches the urologist for insufficient care while on dutasteride therapy as his PSA was not checked regularly. In retrospect, the PSA had increased. Claimer was diagnosed with metastatic PCa and was unsatisfied with the management of his urologist. Before discussing a potential referral with the patient, the urologist had already informed a colleague and sent this colleague patients details. The court decided that the urologist was to blame for insufficient care and for violation of privacy by sending information prematurely. The urologist received an official warning which was published.

Conclusion

Although we were unable to compare cases between the various European countries, we think that we can carefully draw a number of conclusions.

First, the incidence of PSA-related court cases in the Netherlands is low (less than 0.3 pro mille of diagnosed prostate cancer cases over a decade) and stable (1-4 annually). We realise that court cases are often the reflection of professional acts performed 5-10 years earlier. The cases illustrate that judgements are made according to the legal situation of that time and not according to guidelines active at the moment of filing the claim. What was expected to be a major source of legal claims actually turned out to be modest and for urologists even quite favourable.

Secondly, the majority reflects the professional acting of GPs (60%), and the claims successfully filed were double in GPs compared to urologists (2/3rd versus 1/3rd). GPs are dependent on the education and guidelines they obtain from our urologic society. The importance of acting according to guidelines is essential in legal cases, and this is most difficult to our GPs as they have to deal with so many different societies. Current efforts to harmonise the EAU Guidelines with those of national societies appear to be useful to prevent legal references to various texts and in the end might be timesaving for national societies. But most of all, we as urologist need to be aware that we are but an island in the endless sea of patients that visit the GP, and it is our responsibility as a urologic society to comfort and support them the best we can.

The third conclusion reflects the need to communicate well with patients and to note important issues in our professional files shortly after, like: “patient agrees not to screen” or “patient agrees not to treat actively.” Furthermore, once a professional relation with a patient has started, the responsibility of providing information is with the healthcare professional, also when the patient doesn’t pick up the phone.

Just like in many diseases; it serves to prevent a claim.

References

1. CBS – https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/verdeling/