Prognostic biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma

Renal cell carcinomas (RCC) account for more than 90% of renal tumors. RCC are subdivided into histologically defined subtypes. The most common subtypes are clear cell RCC (70-75%), papillary RCC (10-15%) as well as chromophobe RCC (5%) and the benign oncocytomas.

Genetic analyses have shown that these subtypes are characterized by different chromosomal alterations suggesting that each subtype represents a distinct tumor entity with different tumor biology. What does it mean for daily clinical routine? It has been demonstrated by many clinical investigations that the prognosis in patients with renal cell tumors depends on the subtype. Patients with clear cell RCC have the worst prognosis compared to other RCC subtypes based on high frequency of distant metastases.

For a long time, prognostic markers in renal cell carcinomas (RCC) did not really play a role, but they are more and more requested during the last decade because several therapeutic options are available depending on clinical stage. So we need markers allowing the definition of metastatic potential to decide which patients need an aggressive therapy. This is also important in small renal masses in order to decide if it is really necessary to perform surgery, especially in older patients. Here, biomarkers can help to identify aggressive tumors in biopsies.

Furthermore, biomarkers are necessary to select patients for adjuvant therapies.

Until now, risk stratification in localized tumors is based on T-category and grading. But it is known that also small tumors can metastasize in about 20% on one hand, and that not all T3 tumors have a metastatic potential on the other hand. Therefore, a more individual approach characterizing aggressive tumors is requested. This would be of great importance for adjuvant clinical trials.

Many putative prognostic biomarkers have been published for clear cell RCC (ccRCC). But it is clear now, that we need molecular signatures but not single markers because metastasis is a complex process including several changes in the tumor cells and their microenvironment. During the last years, such molecular signatures have been identified on different levels which are really promising. So gene expression signatures have been described by Rini et al. (16 gene signature1) or by Brannon et al.

(ccA vs. ccB)2. These signatures can distinguish aggressive subtypes in ccRCC, especially in localized disease. They can help define an individual risk of metastasis independent on tumor size.

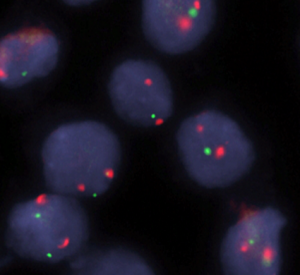

In addition, our group developed a signature of four copy number alterations in ccRCC which can identify primary tumors with high metastatic potential by using a simple FISH-test3. This so called total number of aberrations score (TNSA score) was validated in two independent cohorts. Non-coding RNAs including microRNAs (miRNAs) represent another very interesting type of markers. We and other groups have shown that miRNA signatures are very promising because a limited number of miRNAs compared to mRNAs are necessary to identify aggressive metastatic tumors in RCC4-6. Another advantage of miRNAs is the high stability and the possibility to also use routine formalin fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) samples.

Only little is known for other subtypes like papillary or chromophobe RCC which are characterized by a lower frequency of metastatic disease.

Papillary RCC subtypes

In papillary RCC we have to distinguish two subtypes: type 1 with good prognosis and type 2 which is much more aggressive with shorter survival. The molecular pathology especially of type 2 was almost unknown for many years. Recently, complex TCGA data on pRCC have been published showing that an aggressive type 2 subtype is based on hypermethylation, 9p alterations, specific miRNA changes and partially on FH mutations. Patients with these tumor characteristics are younger and have a very poor prognosis.

Based on these results, it seems possible to identify aggressive renal cell carcinomas by analyzing tumor samples. We have to learn that histopathological subtypes have to be further subdivided into groups with different prognosis based on a specific molecular background.

However, recently published data on tumor heterogeneity in RCC provokes questions about the usefulness of biomarkers analyzed in tumor tissue samples.

Until now, the influence of heterogeneity in primary RCC was analyzed systematically only in one study showing a heterogeneous picture of the ccA and ccB prognostic signature at least in some cases7. In contrast, Rini et al. have not seen a high heterogeneity of the 16 gene prognostic signature in a small cohort1. Therefore, we have to evaluate the quality and accuracy of the published prognostic signatures depending on tumor size as critically discussed by Gerlinger8. In addition, we have to start prospective clinical trials to proof the clinical utility of putative molecular signatures including biopsy material.

In addition, liquid biopsies including free nucleic acids as well as extracellular vesicles are promising biomarkers for prognostic evaluation because they can help overcome problems which are based on intratumoral heterogeneity. But we have to evaluate if liquid biopsies are suitable as prognostic markers in addition to their diagnostic potential.

References

- Rini B, et al. (2015), A 16-gene assay to predict recurrence after surgery in localised renal cell carcinoma: development and validation studies. The lancet oncology. 16, 676-85.

- Brannon AR, et al. (2010), Molecular Stratification of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma by Consensus Clustering Reveals Distinct Subtypes and Survival Patterns.

Genes & cancer. 1, 152-163. - Sanjmyatav J, et al. (2014), Identification of high-risk patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma based on interphase-FISH. British journal of cancer.

110, 2537-43.

Editorial Note: The reference list has been shortened due to space constraints. For a full list, email at communications@uroweb.org

Saturday 25 March

11.50-12.00: Joint Meeting of the EAU Section of Urological Pathology (ESUP) and the EAU Section of Urological Research (ESUR)

Author:

Prof. Dr. Kerstin Junker

Clinic of Urology and Pediatric Urology Saarland University Homburg/Saar (DE)